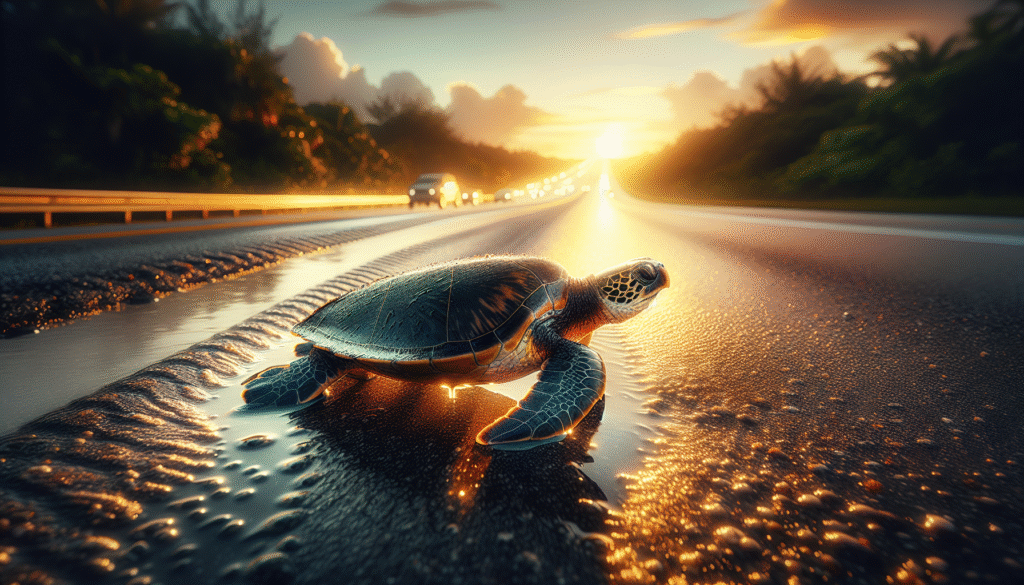

What would you do if you spotted a large sea turtle stranded in the middle of a busy Florida highway?

Florida Man Rescues Stranded Sea Turtle on Busy Highway

This is the story of a Florida man who stopped traffic, assessed the situation, and helped a stranded sea turtle reach safety. You’ll read a clear, practical guide that explains what happened, why it matters, and exactly how you can act safely and legally if you ever encounter a similar situation.

The immediate scene: what likely happened

You approach a chaotic scene: cars slowed or stopped, people out of their vehicles, and a big animal confused on the pavement. In many such incidents, the person who acts first provides calm leadership, keeps the animal safe from traffic, and calls the right people to take over.

When you arrive, you might feel adrenaline and uncertainty. That’s normal. Your priority will be safety — for yourself, the animal, and drivers — and then providing immediate, appropriate care until trained responders arrive.

How the Florida man likely assessed the situation

First, he checked whether the turtle was alive, whether it was injured, and whether it represented an immediate traffic hazard. He then signaled traffic to slow, used hazard lights and his phone’s flashlight, and called local authorities or wildlife responders.

You should do the same: pause, evaluate at a safe distance, and use your phone to alert emergency services or the wildlife network. Acting calmly reduces risk for everyone and gives you the best chance to help effectively.

Why quick action matters

Sea turtles face many threats on land and at sea, from vehicle strikes to dehydration to predation. A few minutes can mean the difference between survival and fatal trauma. Your timely intervention can prevent further injury and connect the turtle with experts who can provide necessary veterinary care.

When you act quickly and correctly, you contribute to the conservation of species that are protected and often endangered.

Why sea turtles end up on roads

Sea turtles sometimes wander onto roads for reasons that include nesting attempts, disorientation, injury, or following flooded habitats. In coastal areas, roads often run between beaches and inland waterways, creating dangerous crossing points.

During nesting season, female turtles may attempt to reach inland nesting sites at night and become confused by artificial lights or travel across roadways. Juveniles or injured turtles from nearby wetlands or estuaries may also end up on roads when tides change or storms alter their habitats.

Human and environmental causes

Artificial lighting, coastal development, boat strikes, and habitat fragmentation all play a role. Storms and flooding can displace turtles and push them out of usual habitats, and temperature extremes can cause cold-stunning in species that require warm water.

You can reduce risk by supporting local conservation measures and being aware of seasonal patterns that increase turtle movement near roads.

Safety first: protecting yourself, the turtle, and drivers

Your personal safety is paramount. Before you attempt any rescue, secure the scene as much as possible. Put on your hazard lights, set up any emergency triangles if available, and move to a position that allows you to monitor traffic while keeping a safe distance.

Approach the turtle slowly and from the side rather than from the front to avoid startling it. Never put yourself between oncoming traffic and the turtle. If traffic conditions are hazardous, call 911 and wait for police assistance to control traffic.

Traffic control and calling for help

If you can do so safely, use your hazard lights and have a second person assist with traffic control while waiting for responders. If there’s no immediate danger of being struck, calling local law enforcement or the local wildlife agency is preferable because they can provide traffic control and coordinate a trained response.

When you call, describe the exact location, the species if you can identify it, the turtle’s approximate size, and whether it’s injured or alive. Clear information saves precious time.

Personal protective measures and equipment

You don’t need fancy gear to help, but a few items are useful: gloves to protect your hands and the turtle’s shell from oils or contamination, a towel to shield eyes and head, and a cardboard box or sturdy container for transport if needed. Avoid bare hands if the turtle is large and may bite or scratch.

If you wear a reflective vest or bright clothing, you’ll be more visible to traffic. Use your phone light if visibility is low, but avoid shining bright lights in the turtle’s eyes.

How to handle and move a sea turtle safely

Moving a sea turtle requires care and technique. You must support the turtle’s body evenly and avoid lifting by flippers, tail, or the shell edge. For small turtles (carapace length under about 12 inches), you can often lift them with one hand under the plastron (bottom shell) and the other supporting the carapace (top shell). For medium and large turtles, you’ll need at least two people.

Always keep the turtle level and close to the ground or inside a container. Never attempt to carry a large sea turtle by yourself; ask for assistance from others at the scene or wait for trained responders.

Lifting technique by size

- Small turtles (under ~12 inches): Place one hand under the plastron and the other over the carapace. Keep the turtle level and move it to safety or into a ventilated container.

- Medium turtles (12–30 inches): Two people should each place one hand under the plastron and one hand on the carapace to support weight. Move slowly and communicate clearly during lifting.

- Large turtles (over 30 inches): These often weigh dozens of pounds. Do not attempt to lift alone. Support with at least two helpers or wait for professional responders. If the turtle’s flippers are thrashing, secure them gently with towels before lifting.

What not to do

Avoid the following actions because they can cause severe harm:

- Don’t lift the turtle by its flippers, tail, or head.

- Don’t try to flip a turtle over on its shell unless it’s necessary to prevent immediate harm; flipping can stress or injure it.

- Don’t pour water into the turtle’s mouth or nostrils.

- Don’t try to feed or give medications.

- Don’t attempt invasive first aid unless you are trained.

Quick reference table: Do’s and Don’ts

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Do call local wildlife authorities or 911 if traffic is hazardous. | Don’t attempt to move the turtle if doing so would put you or others at risk. |

| Do wear gloves and use a towel or blanket to shield the head. | Don’t lift by flippers, tail, or the shell rim. |

| Do keep the turtle shaded and cool, especially in heat. | Don’t pour water into its mouth or nasal openings. |

| Do document location and condition for responders. | Don’t attempt to self-treat serious injuries. |

| Do transport in a ventilated container if instructed by professionals. | Don’t keep the turtle as a pet or transport long distances without authorization. |

Identifying species and doing a basic health assessment

You don’t need to be a biologist to give useful information to responders. A few key characteristics help identify common Florida sea turtles: carapace shape, presence of a single or double scute pattern, coloration, and the presence of a pronounced head (leatherbacks look very different from hard-shelled species).

Loggerheads have broad heads and reddish-brown carapaces. Greens are more heart-shaped and often greenish or brown. Kemp’s ridley are small and round with a grayish shell, and leatherbacks are large with leathery, ridged backs and lack a hard carapace.

Species quick-identification table

| Species | Key features | Typical size |

|---|---|---|

| Loggerhead (Caretta caretta) | Broad head, reddish-brown carapace, 5–9 scutes | 2.5–3.5 ft |

| Green turtle (Chelonia mydas) | Smooth, heart-shaped shell, greenish fat under skin | 3–4 ft |

| Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempii) | Small, round, grayish shell, one of the smallest species | 2–2.5 ft |

| Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) | Large, dark, flexible carapace with longitudinal ridges | Up to 6–7 ft |

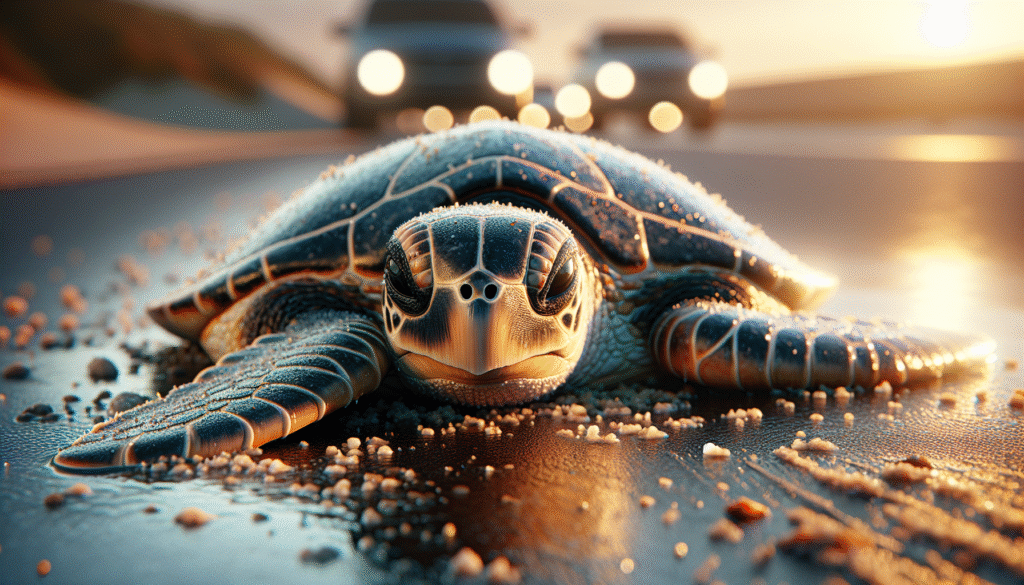

When you call for help, report what you see: size (approximate), coloration, shell condition (cracks, punctures), presence of blood or obvious injuries, and behavior (lethargic, trying to crawl, breathing irregularly).

Signs of injury or distress you should report

Look for deep carapace or plastron fractures, exposed tissue, bleeding, gasping or irregular breathing, entanglement lines, fishing hooks, or evidence of boat strike (crush wounds). Also report if the turtle cannot right itself, appears cold-stunned (lethargic, floating strangely), or shows signs of neurological damage such as lack of coordination.

These observations help responders prioritize care and determine whether on-site stabilization is needed.

Legal protections and what you’re allowed to do

Sea turtles and their eggs are protected under federal and state laws, including the U.S. Endangered Species Act and Florida state wildlife regulations. That means you cannot take a turtle home, keep it, or move it long distances without proper authorization and permits.

However, you are allowed — and encouraged — to provide immediate, noninvasive assistance to prevent imminent harm. This includes moving a turtle out of immediate danger, providing shade, and reporting the situation to authorities.

What to tell authorities when you call

When contacting wildlife agencies or 911, give precise information:

- Exact location (mile markers, landmarks, GPS coordinates if possible)

- Whether the turtle is alive or deceased

- Approximate size and species if known

- Visible injuries or entanglement

- Whether traffic control is required

Clear details speed response and reduce confusion on arrival.

Transporting a live turtle to rehabilitation

If authorities advise you to transport the turtle to a rehabilitation facility, follow their directions exactly. Use a sturdy box or crate that allows ventilation and supports the turtle’s body. Line the container with damp towels to maintain humidity and prevent slipping. Keep the turtle level to avoid stressing internal organs, and secure the box so it won’t shift in your vehicle.

Avoid prolonged car rides and extreme temperatures. Do not place the turtle in direct sunlight or in an air-conditioned stream that could chill it. Instead, maintain a moderate temperature appropriate for the species; ask the responder what range is safest.

Preparing your vehicle and container

- Choose a quiet, shaded spot in your vehicle, such as the floor of the back seat, to reduce stress.

- Use towels or non-slip mats to stabilize the container.

- Keep the vehicle’s interior at a stable temperature; avoid extremes.

- Drive directly to the designated facility and contact them on the way to alert their staff.

If the turtle is large or the condition is severe, wait for professional transport. Many wildlife organizations have trained transport teams and specialized equipment.

What to do if the turtle is deceased or cannot be moved

If the turtle is deceased, you should still report the location and condition so responders can determine cause and collect data. Do not attempt to bury or dispose of the turtle yourself; local authorities or stranding networks typically handle carcass collection, which is important for research and monitoring.

If the turtle is too large or you’re unable to move it without risk, secure the area as best you can, keep people and pets away, and wait for emergency personnel or wildlife responders.

Collecting useful information when you cannot move the turtle

Take photos (from a safe distance) showing the turtle and surrounding area, note the time and weather conditions, and log any nearby hazards like downed power lines or active fires. This information assists responders and contributes to conservation data.

What rehabilitation centers do and why they matter

Rehabilitation centers provide medical assessment, treatment for injuries or entanglement, supportive care for illnesses like cold-stunning or fibropapillomatosis, and eventual release back into suitable habitat. They also track data that informs conservation strategy and research.

If you bring a turtle to rehab, certified veterinary teams will stabilize the animal, determine whether surgery or long-term care is needed, and plan recovery that minimizes stress and maximizes chances of survival.

Typical rehabilitation timeline and outcomes

Recovery varies by injury and species. Minor injuries may take weeks, while severe trauma can require months or longer. Many rehabilitated turtles are successfully released, but some may have permanent disabilities that prevent survival in the wild and require long-term care.

Your prompt, informed action at the scene increases the likelihood of a positive rehab outcome.

How your action made a difference

By stopping to help, the Florida man reduced the immediate risk of vehicle strikes, protected the turtle from overheating and predators, and connected the animal with professional care. Every rescue creates a ripple effect: it saves an individual and contributes to broader conservation efforts through data collection and public awareness.

If you act correctly in similar situations, you help protect species that face multiple threats and inspire others to respond responsibly.

Preventing future road incidents

Communities can reduce road-related sea turtle incidents through thoughtful planning and public awareness campaigns. Effective measures include installing warning signs in known crossing areas, limiting nighttime lighting near nesting beaches, and creating wildlife underpasses or crossing structures where feasible.

You can support local conservation partners, report priority areas to community planners, and encourage responsible beach lighting practices to reduce disorientation and road crossings.

Long-term solutions and your role

Signage, lowered speed limits during nesting season, and coordinated volunteer patrols can mitigate risks. You can volunteer for beach patrols, support zoning regulations that preserve nesting habitat, and share best practices with neighbors to reduce artificial lighting.

Your advocacy and on-the-ground involvement help protect future turtles and reduce the need for emergency rescues.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

You probably have practical questions after reading this. These FAQs provide concise answers to common concerns you’ll face at the scene.

Q: Can I keep a rescued sea turtle until I find a rehab center?

No. Sea turtles are protected species, and keeping one without a permit is illegal. Provide short-term care only as directed by wildlife professionals and transport to an authorized facility if instructed.

Q: What if the turtle bites me or scratches me?

Sea turtles can bite in defense, so wear gloves if you must handle one. If bitten or scratched, clean the wound thoroughly and seek medical attention, as marine organisms can cause infection.

Q: Is it safe to spray the turtle with water?

You can lightly mist or keep a turtle shaded to prevent overheating, but avoid flooding the turtle or pouring water into its mouth or nostrils. For cold-stunned turtles, do not warm them rapidly; wait for responder instructions.

Q: How quickly should I act?

Act immediately if the turtle is in traffic or exposed to heat. If it’s safe to move the turtle out of immediate danger and you can do so without risk, that should be your first step. Then call responders for follow-up.

Q: Will moving a turtle cause more harm?

If done correctly and conservatively, moving a turtle out of immediate danger reduces the risk of vehicular trauma. The key is to avoid invasive handling and to move the turtle only when it’s safe for you and the animal.

Community resources and who to contact

Every coastal region has different organizations and hotlines. You should locate the nearest wildlife agency, sea turtle stranding network, or certified rehabilitation center in your area and save the contact information on your phone.

When in doubt, call 911 for immediate traffic or safety concerns; they can coordinate with wildlife authorities and provide on-site assistance.

What information to have ready

Keep a short checklist on your phone for emergencies: the local wildlife hotline, nearby rehab centers, the non-emergency police number, and concise steps you’ll follow at the scene. This quick reference saves time and stress during a real event.

Final checklist you can use at the scene

This short, actionable checklist helps you act confidently and responsibly.

- Ensure your own safety; park safely and turn on hazard lights.

- Assess the scene from a safe distance; determine if traffic control is needed.

- Call 911 or the local wildlife authority; relay exact location and turtle status.

- If safe, approach slowly and check whether the turtle is alive and breathing.

- Wear gloves and use a towel to shield the head if you must handle the turtle.

- Support the turtle’s weight evenly; do not lift by flippers or tail.

- Move the turtle out of traffic to a shaded, cool area or to a ventilated container if directed.

- Transport only if instructed and to the location specified by responders.

- Provide photos and detailed observations for responders and rehabilitation staff.

- Follow up with the wildlife agency to learn outcomes and contribute data.

Closing thoughts: being prepared makes you part of the solution

Seeing a sea turtle stranded on a busy highway can be startling, but your calm, informed response can make a lifesaving difference. By prioritizing safety, contacting the appropriate responders, and following best-practice handling steps, you help protect an iconic species and strengthen community stewardship.

You don’t need special training to be helpful — just preparation, caution, and knowledge. Keep local numbers handy, learn the simple handling tips outlined here, and be ready to act with care if you ever encounter a turtle in distress. Your actions matter to the individual animal and to the broader conservation effort that keeps Florida’s beaches and waterways healthy for future generations.